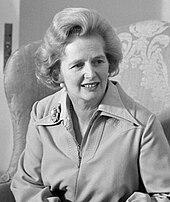

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher, LG, OM, PC, FRS (née Roberts; born 13 October 1925) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 until 1990. She was born in Grantham in Lincolnshire, and studied chemistry at Somerville College, Oxford, before qualifying as a barrister. In the 1959 general election she became the MP for Finchley as a Conservative. Edward Heath appointed Thatcher Secretary of State for Education and Science in his 1970 government. In 1975 she became Leader of the Conservative Party, the first woman leader of a major UK political party. Following the 1979 general election she became Britain's first female Prime Minister.

She entered 10 Downing Street determined to reverse what she perceived as a precipitate national decline.[2] Her political philosophy and economic policies emphasised deregulation, particularly of the financial sector, flexible labour markets, the sale or closure of state owned companies, and the withdrawal of subsidies to others. Thatcher's popularity went into decline amid recession and high unemployment, although economic recovery and the 1982 Falklands War brought a resurgence of support and she was re-elected in 1983. She survived an assassination attempt in 1984. She took a hard line against trade unions, and her tough rhetoric in opposition to the Soviet Union earned her the nickname of the "Iron Lady". Thatcher was re-elected for a third term in 1987, but her poll tax was widely unpopular and her views on the European Community were not shared by others in her Cabinet. She resigned as Prime Minister and party leader in November 1990 after Michael Heseltine's challenge to her leadership of the Conservative Party.

Thatcher's tenure as Prime Minister was the longest since that of Lord Salisbury, and the longest continuous period in office since Lord Liverpool in the early 19th century.[3] She holds a life peerage as Baroness Thatcher, of Kesteven in the County of Lincolnshire, which entitles her to sit in the House of Lords.

Early life and education

Margaret Hilda Roberts was born on 13 October 1925 to Alfred Roberts, originally from Northamptonshire, and his wife, the former Beatrice Ethel Stephenson from Lincolnshire.[4] She spent her childhood in Grantham, Lincolnshire, where her father owned two grocery shops.[5] She and her older sister Muriel were raised in the flat above the larger of the two, located near the railway line.[5] Her father was active in local politics and religion, serving as an alderman and a Methodist lay preacher. He came from a Liberal family but stood—as was then customary in local government—as an Independent. He lost his position as alderman in 1952 after the Labour Party won its first majority on Grantham Council in 1950.[6]Margaret Roberts' father brought her up as a strict Methodist.[7] She attended Huntingtower Road Primary School and won a scholarship to Kesteven and Grantham Girls' School.[8] Her school reports showed hard work and continual improvement; her extracurricular activities included the piano, hockey, poetry recitals, swimming and walking.[9][10] In her upper sixth year she applied for a scholarship to study chemistry at Somerville College, Oxford; she was initially rejected, but was offered a place when another candidate withdrew.[11][12] She arrived in Oxford in 1943, and graduated in 1947 with Second Class Honours in the four-year Chemistry Bachelor of Science degree; in her final year she specialised in crystallography under the supervision of Dorothy Hodgkin.[13][14]

Roberts became President of the Oxford University Conservative Association in 1946.[15][16] During her time at university she became influenced by Friedrich von Hayek's 1944 work The Road to Serfdom, which condemned economic intervention by government as a precursor to an authoritarian state.[17]

Roberts moved to Colchester in Essex after graduating, to work as a research chemist for BX Plastics.[18] She joined the local Conservative Association and attended the party conference at Llandudno in 1948, as a representative of the University Graduate Conservative Association.[19] In January 1949, a friend from Oxford who was working for the Dartford Conservative Association in Kent, told her that they were looking for candidates.[19] Shortly afterwards Roberts was selected as the Conservative candidate, and moved to Dartford to stand for election as a Member of Parliament. There she was employed by J. Lyons and Co., developing methods for the preservation of ice cream.[19]

Early political career

In the 1950 and 1951 general elections Margaret Thatcher campaigned for the safe Labour seat of Dartford, where she attracted media attention as the youngest and the only female candidate.[20][21] She lost to Norman Dodds, but reduced the Labour majority by 6,000.[22] While campaigning in Kent in 1950 she met Denis Thatcher, a wealthy divorced businessman who ran his family's firm. They married in 1951.[23] Denis funded his wife's studies for the bar;[24] she qualified as a barrister in 1953 and specialised in taxation.[25] That same year her twins, Carol and Mark, were born.[26]Member of Parliament (1959–1970)

Thatcher began to look for a safe Conservative seat in the mid-1950s. She was narrowly rejected as the candidate for Orpington in 1955,[26] but was eventually selected for Finchley in April 1958. She won the seat after a hard campaign in the 1959 election and was elected as a Member of Parliament (MP).[27] Her maiden speech was in support of her Private Member's Bill (Public Bodies (Admission to Meetings) Act 1960), requiring local authorities to hold their council meetings in public. In 1961 she went against the Conservative Party's official position by voting for the restoration of birching.[28]In October 1961 Thatcher was promoted to the front bench as Parliamentary Undersecretary at the Ministry of Pensions and National Insurance in Harold Macmillan's administration.[29] After the loss of the 1964 election she became Conservative spokesman on Housing and Land, in which position she advocated the Conservative policy of allowing tenants to buy their council houses.[30] She moved to the Shadow Treasury team in 1966, and as Treasury spokesman opposed Labour's mandatory price and income controls, arguing that they would produce contrary effects to those intended and distort the economy.[30]

At the Conservative Party Conference of 1966 she criticised the high-tax policies of the Labour Government as being steps "not only towards Socialism, but towards Communism".[30] She argued that lower taxes served as an incentive to hard work.[30] Thatcher was one of few Conservative MPs to support Leo Abse's Bill to decriminalise male homosexuality and voted in favour of David Steel's Bill to legalise abortion,[1] as well as a ban on hare coursing.[31][32] She supported the retention of capital punishment and voted against the relaxation of divorce laws.[33]

In 1967 she was selected by the Embassy of the United States in London to take part in the International Visitor Leadership Program (then called the Foreign Leader Program), a professional exchange programme that gave her the opportunity to spend about six weeks visiting various US cities, political figures, and institutions such as the International Monetary Fund.[34] Thatcher joined the Shadow Cabinet later that year as Shadow Fuel spokesman. Shortly before the 1970 general election she was promoted to Shadow Transport, and then to Education.[35]

Education Secretary (1970–1974)

The Conservative party under Edward Heath won the 1970 general election, and Thatcher was appointed Secretary of State for Education and Science. In her first months in office she attracted public attention as a result of the administration's attempts to cut spending. She gave priority to academic needs in schools,[36] and imposed public expenditure cuts on the state education system, resulting in the abolition of free milk for schoolchildren aged seven to eleven.[37] She held that few children would suffer if schools were charged for milk, but she agreed to provide younger children with a third of a pint daily, for nutritional purposes.[37] Her decision provoked a storm of protest from the Labour party and the press,[38] and led to the moniker "Margaret Thatcher, Milk Snatcher".[37] Thatcher wrote in her autobiography: "I learned a valuable lesson [from the experience]. I had incurred the maximum of political odium for the minimum of political benefit."[38]Thatcher's term of office was marked by several proposals for more local education authorities to close grammar schools and to adopt comprehensive secondary education, but she was committed to a tiered secondary modern–grammar school system of education, and she was determined to preserve grammar schools.[36]

Leader of the Opposition (1975–1979)

Margaret Thatcher, elected as Leader of the Opposition on 18 September 1975

Thatcher began at this time regularly to attend lunches at the Institute of Economic Affairs, a think tank founded by the poultry magnate Antony Fisher, the man who brought battery farming to Britain and a disciple of Friedrich von Hayek; she had begun visiting the IEA and reading its publications during the early 1960s. She came in contact there with Ralph Harris and Arthur Seldon, who became influences on her. Thatcher now became the face of the ideological movement that opposed the welfare state Keynesian economics they believed was weakening Britain. The institute's pamphlets proposed less government, lower taxes, and more freedom for business and consumers.[43]

Thatcher began to work on her voice and screen image. "The hang-up has always been the voice" wrote the critic Clive James, in The Observer. "Not the timbre so much as, well, the tone – the condescending explanatory whine which treats the squirming interlocutor as an eight-year-old child with learning deficiencies. News Extra rolled a clip from May 1973 demonstrating the Thatcher sneer at full pitch. She sounded like a cat sliding down a blackboard." She worked to change this image and James acknowledged: "She's cold, hard, quick and superior, and smart enough to know that those qualities could work for her instead of against."[44]

On 19 January 1976 Thatcher made a speech in Kensington Town Hall in which she made a scathing attack on the Soviet Union.

In response, the Soviet Defence Ministry newspaper Krasnaya Zvezda (Red Star) gave her the nickname "Iron Lady".[45] She took delight in the name and it soon became associated with her image.The Russians are bent on world dominance, and they are rapidly acquiring the means to become the most powerful imperial nation the world has seen. The men in the Soviet Politburo do not have to worry about the ebb and flow of public opinion. They put guns before butter, while we put just about everything before guns.[45]

Despite an economic recovery in the late 1970s, the Labour Government faced public unease about the direction of the country and a damaging series of strikes during the winter of 1978–79, popularly dubbed the "Winter of Discontent". The Conservatives attacked the government's unemployment record, using advertising hoardings with the slogan Labour Isn't Working. A general election was called after James Callaghan's government lost a motion of no confidence in early 1979. The Conservatives won a 44-seat majority in the House of Commons, and Margaret Thatcher became the United Kingdom's first female Prime Minister.

Prime Minister (1979–1990)

Main article: Premiership of Margaret Thatcher

Thatcher's Ministry meets with Reagan's Cabinet at the White House, 1981

She took office in the final decade of the Cold War, an era of strategic confrontation between the Western powers and the Soviet Union and its Warsaw Pact satellites. During her first year as Prime Minister she supported NATO's decision to deploy US cruise and Pershing missiles in Western Europe,[46] and permitted the United States to station more than 160 nuclear cruise missiles at Greenham Common, triggering mass protests by the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.[46]Where there is discord, may we bring harmony. Where there is error, may we bring truth. Where there is doubt, may we bring faith. And where there is despair, may we bring hope.

Thatcher narrowly escaped injury in an assassination attempt at a Brighton hotel early in the morning of 12 October 1984, carried out by the Provisional Irish Republican Army.[47] Five people were killed, including the wife of Cabinet Minister John Wakeham. Thatcher was staying at the hotel to attend the Conservative Party Conference, and insisted that the event open as scheduled the following day.[47] She delivered her speech as planned,[48] a gesture which won widespread approval across the political spectrum, and enhanced her personal popularity with the public.[49]

As Prime Minister, Thatcher met weekly with Queen Elizabeth II to discuss government business,[50] and their relationship came under close scrutiny.[51] In July 1986 the Sunday Times reported claims attributed to the Queen's advisers of a "rift" between Buckingham Palace and Downing Street "over a wide range of domestic and international issues".[52][53] The Palace issued an official denial, heading off speculation about a possible constitutional crisis.[53] After Thatcher's retirement a senior Palace source again dismissed as "nonsense" the "stereotyped idea" that she had not got along with the Queen or that they had fallen out over Thatcherite policies.[54] Thatcher herself declared that "stories of clashes between 'two powerful women' were too good not to make up ... I always found the Queen's attitude towards the work of the Government absolutely correct".[55]

Economy and taxation

Thatcher's economic policy was influenced by monetarist thinking and economists such as Milton Friedman and Friedrich von Hayek.[56] Together with Chancellor of the Exchequer Geoffrey Howe, she lowered direct taxes on income and increased indirect taxes.[57] She increased interest rates to slow the growth of the money supply and thereby lower inflation,[56] and placed limits on the printing of money.[58] She introduced cash limits on public spending, and reduced expenditures on social services such as education and housing.[57] Her cuts in higher education spending resulted in her being the first Oxford-educated post-war Prime Minister to be refused an honorary doctorate by the University of Oxford.[59]| GDP and public spending by functional classification | % change in real terms 1979/80 to 1989/90[60] |

|---|---|

| GDP | +23.3 |

| Total government spending | +12.9 |

| Law and order | +53.3 |

| Employment and training | +33.3 |

| Health | +31.8 |

| Social security | +31.8 |

| Transport | −5.8 |

| Trade and industry | −38.2 |

| Housing | −67.0 |

| Defence | −3.3[61] |

As the recession of the early 1980s deepened, Thatcher increased taxes[64] despite concerns expressed in a statement signed by 364 leading economists and issued towards the end of March 1981.[65] Unemployment soared, and by December her job approval rating had fallen to 25%, the lowest of her premiership and lower than recorded for any previous Prime Minister.[66][page needed]

By early 1982 the economic slump had bottomed out;[66][page needed] inflation was down to 8.6% from a high of 18%, but unemployment was over 3 million for the first time since the 1930s.[67] By 1983 overall economic growth was stronger and inflation and mortgage rates were at their lowest levels since 1970, although manufacturing output had dropped by 30% since 1978[68] and unemployment remained high, peaking at 3.3 million in 1984.[69]

Thatcher replaced local government taxes with a Community Charge or "poll tax", in which property tax rates were made uniform, in that the same amount was charged to every individual resident, and the residential property tax was replaced by a head tax at a rate set by local authorities.[70] The new tax was introduced in Scotland in 1989 and in England and Wales the following year,[71] and proved to be among the most unpopular policies of her premiership,[70] culminating in a public demonstration that turned into rioting in Trafalgar Square, London, on 31 March 1990; more than 100,000 protesters attended and more than 400 people were arrested.[72] Thatcher remained confident that, as with her other major reforms, the initial public opposition would eventually turn into support.[73]

The term "Thatcherism" came to refer to her policies as well as aspects of her ethical outlook and personal style, including moral absolutism, nationalism, interest in the individual, and an uncompromising approach to achieving political goals.[58] American author Claire Berlinski, who wrote the biography There Is No Alternative: Why Margaret Thatcher Matters, argues repeatedly throughout the volume that it was this Thatcherism, specifically her focus on economic reform, that set the United Kingdom on the path to recovery and long term growth.[citation needed]

Foreign affairs

On 2 April 1982, the ruling military junta in Argentina invaded the British overseas territories of Falkland Islands and South Georgia, triggering the Falklands War.[74] The following day, Thatcher sent a naval task force to recapture the islands and eject the invaders.[74] Argentina surrendered on 14 June and the operation was hailed a great success, notwithstanding the deaths of 255 British servicemen and three Falkland Islanders. Argentinian deaths totalled 649, half of them after the cruiser ARA General Belgrano was torpedoed by the nuclear submarine HMS Conqueror.[75] The "Falklands factor", an economic recovery beginning early in 1982, and a bitterly divided Labour opposition contributed to Thatcher's second election victory in 1983.[76]Thatcher's preference for defence ties with the United States was demonstrated in the Westland affair of January 1986, when she acted with colleagues to allow the helicopter manufacturer Westland, a defence contractor, to refuse an offer from the Italian firm Agusta in favour of the management's preferred option, a link with Sikorsky Aircraft Corporation of the United States. Defence Secretary Michael Heseltine, who had pushed the Agusta deal, resigned in protest.

In April 1986 Thatcher, after expressing initial reservations, permitted US F-111s to use RAF bases for the bombing of Libya in retaliation for the alleged Libyan bombing of a Berlin discothèque,[77] citing the right of self-defence under Article 51 of the UN Charter.[78] Thatcher told the House of Commons: "The United States has more than 330,000 members of her forces in Europe to defend our liberty. Because they are there they are subject to terrorist attack. It is inconceivable that they should be refused the right to use American aircraft and American pilots in the inherent right of self-defence to defend their own people."[79]

The United Kingdom was the only nation to provide support and assistance for the US action.[79] Polls suggested that more than two out of three people disapproved of Thatcher's decision.[80] Later that year the United States Congress approved an extradition treaty designed to stop IRA operatives evading extradition. The United States Senate only ratified this treaty when Reagan explicitly mentioned Britain's support for the bombing of Libya.[81]

Thatcher was one of the first Western leaders to respond warmly to reformist Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. Following the Reagan-Gorbachev summit meetings from 1985 to 1988, as well as multiple reforms enacted by Gorbachev in the USSR, Thatcher declared in November 1988, "We're not in a Cold War now" but rather in a "new relationship much wider than the Cold War ever was".[82]

Thatcher's antipathy towards European integration became more pronounced during her premiership, particularly after her third election victory in 1987. At Bruges in 1988, she made a speech in which she outlined her opposition to proposals from the European Community, forerunner of the European Union, for a federal structure and increased centralisation of decision-making.[83] Though she had supported British membership in the EC, Thatcher believed that the role of the organisation should be limited to ensuring free trade and effective competition, and feared that the EC approach to governing was at odds with her views on smaller government and deregulatory trends;[84] in 1988, she remarked, "We have not successfully rolled back the frontiers of the state in Britain, only to see them re-imposed at a European level, with a European super-state exercising a new dominance from Brussels".[84]

Thatcher was firmly opposed to British membership of the Exchange Rate Mechanism, a precursor to European monetary union, believing that it would constrain the UK economy,[85] despite the urging of her Chancellor of the Exchequer Nigel Lawson and Foreign Secretary Geoffrey Howe.[86]

Thatcher initially opposed German reunification, telling Premier Gorbachev that "this would lead to a change to postwar borders, and we cannot allow that because such a development would undermine the stability of the whole international situation and could endanger our security". She expressed concern that a united Germany would align itself more closely with the Soviet Union and move away from NATO.[87]

Thatcher was visiting the United States when she received word that Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein had invaded neighbouring Kuwait.[88] When she met with US President George H. W. Bush, who had succeeded Reagan in 1989, Bush asked her for her opinion. She recommended intervention[88] and put pressure on Bush to deploy troops in the Middle East to drive the Iraqi army out of Kuwait.[89] Bush was somewhat apprehensive about the plan, prompting Thatcher to remark to him during a telephone conversation that "This was no time to go wobbly!"[90] Thatcher's government provided military forces to the international coalition in the build-up to the Gulf War.[91]

Industrial relations

Thatcher was committed to reducing the power of the trade unions, whose leadership she accused of undermining parliamentary democracy and economic performance through strike action.[92] Several unions launched strikes in response to legislation introduced to curb their power, but resistance eventually collapsed.[46] Only 39% of union members voted for Labour in the 1983 general election.[93] According to the BBC, Thatcher "managed to destroy the power of the trade unions for almost a generation".[94]The number of stoppages across the United Kingdom peaked at 4,583 in 1979, with over 29 million working days lost. In 1984, the great year of industrial confrontation with the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), there were 1,221 stoppages and over 27 million working days lost. Stoppages then fell steadily through the rest of Thatcher's premiership, to 630 by 1990, with under 2 million working days lost, and continued to fall thereafter.[66][page needed] Trade union membership also fell, from over 12 million in 1979 to 8.4 million in 1990.[66][page needed]

The miners' strike was the biggest confrontation between the unions and the Thatcher government. In March 1984[95] two-thirds of the country's miners downed tools[96][97] in protest against against National Coal Board's proposals to close 20 of the 174 state-owned mines and cut 20,000 jobs out of 187,000.[98][96][99] Thatcher refused to meet the union's demands,[58] saying: "We had to fight the enemy without in the Falklands. We always have to be aware of the enemy within, which is much more difficult to fight and more dangerous to liberty."[94]

After a year out on strike, in March 1985, the National Union of Mineworkers leadership conceded without a deal. The cost to the economy was estimated to be at least £1.5 billion. and the strike was blamed for much of the pound's fall against the US dollar.[100] The government proceeded to close 25 unprofitable pits in 1985; by 1992, a total of 97 pits had been closed,[101] with the remaining being sold off and privatised in 1994.[102] The eventual closure of 150 collieries, not all of which were losing money, resulted in the loss of tens of thousands of jobs and devastated entire communities.[101][103]

Privatisation

The policy of privatisation has been called "a crucial ingredient of Thatcherism".[104] After the 1983 election the sale of large state utilities to private companies accelerated.[105]The process of privatisation, especially the preparation of nationalised industries for privatisation, was associated with marked improvements in performance, particularly in terms of labour productivity,[106] though it is not clear how far this can be attributed to the merits of privatisation itself. Marxian economist Andrew Glyn believed that the "productivity miracle" observed in British industry under Thatcher was achieved not so much by increasing the overall productivity of labour as by reducing workforces and increasing unemployment.[107] A number of the privatised industries, such as gas, water and electricity, were natural monopolies for which privatisation involved little increase in competition. Furthermore, the privatised industries that underwent improvements often did so while still under state ownership. For instance, British Steel made great gains in profitability while still a nationalised industry under the government-appointed chairmanship of Ian MacGregor, who faced down trade-union opposition to close plants and reduce the workforce by half.[108] Regulation was also significantly expanded to compensate for the loss of direct government control, with the foundation of regulatory bodies like Ofgas, Oftel and the National Rivers Authority.[109] Overall, there was no clear pattern between the degree of competition, regulation and performance among the privatised industries.[110]

The privatisation of public assets was combined with deregulation of finance in an attempt to fuel economic growth. In 1979 Geoffrey Howe abolished Britain's exchange controls to allow more capital to be invested in foreign markets, and the Big Bang of 1986 removed many restrictions on the activities of the London Stock Exchange. The Thatcher government encouraged growth in the finance and service sectors to replace Britain's ailing manufacturing industry. Political economist Susan Strange called this new financial growth model "casino capitalism", reflecting her view that speculation and financial trading were becoming a more important part of the economy than industry.[111]

Northern Ireland

In 1981 a number of Provisional IRA and Irish National Liberation Army prisoners in Northern Ireland's Maze Prison began a hunger strike in an effort to regain the status of political prisoners that had been removed five years earlier under the preceding Labour government.[112] Bobby Sands began the strike, saying that he would fast until death unless prison inmates won concessions over their living conditions.[112] Thatcher refused to countenance a return to political status for the prisoners, declaring "Crime is crime is crime; it is not political".[112] Despite this public stance, the British government made private contact with republican leaders in a bid to bring the hunger strikes to an end.[113] After Sands and nine more men had starved to death and the strike had ended, some rights were restored to paramilitary prisoners, though official recognition of political status was not granted.[114] Violence in Northern Ireland significantly escalated during the hunger strike. Due to her actions Thatcher became an Irish Republican hate figure of Cromwellian proportions, with Sinn Féin politician Danny Morrison describing her as "the biggest bastard we have ever known" at the 1982 Sinn Féin Ard Fheis (party conference).[115]Later that year, Thatcher and Irish Taoiseach Garret FitzGerald established the Anglo-Irish Inter-Governmental Council, a forum for meetings between the two governments.[116] On 15 November 1985, Thatcher and FitzGerald signed the Hillsborough Anglo-Irish Agreement; the first time a British government gave the Republic of Ireland an advisory role in the governance of Northern Ireland. The Ulster Says No movement attracted 100,000 to a protest rally in Belfast.[117] Ian Gow resigned as Minister of State in the HM Treasury over the signing of the agreement.[118][119]

Resignation

Thatcher was challenged for the leadership of the Conservative Party by virtually unknown backbench MP Sir Anthony Meyer in the 1989 leadership election.[120] Of the 374 Conservative MPs eligible to vote 314 voted for Thatcher and 33 for Meyer.[120] Her supporters in the Party viewed the result as a success, and rejected suggestions that there was discontent within the Party.[120]During her premiership, the longest continuous period of office of any Prime Minister in the 20th century, Thatcher had, on average, the second-lowest approval rating, at 40%, of any post-war Prime Minister. Polls consistently showed that she was less popular than her party.[121] A self-described conviction politician, Thatcher always insisted that she did not care about her poll ratings, pointing instead to her unbeaten election record.[122]

Opinion polls in September 1990 found that Labour had established a 14% advantage over the Conservatives,[123] and by November the Conservatives had been trailing Labour for 18 months.[121] These ratings, together with Thatcher's combative personality and willingness to override colleagues' opinions, contributed to discontent within the Conservative party.[124]

On 1 November 1990, Geoffrey Howe, for 15 years one of Thatcher's most "loyal and self-effacing" supporters, resigned from his position as Deputy Prime Minister over her refusal to agree to a timetable for British membership of the single currency.[123][125] In his resignation speech, Howe commented on Thatcher's European stance: "It is rather like sending your opening batsmen to the crease only for them to find the moment that the first balls are bowled that their bats have been broken before the game by the team captain."[126] His resignation was later regarded as having dealt a "fatal blow" to Thatcher's premiership.[127]

A few days later Heseltine mounted a challenge for the leadership of the Conservative Party, after five separate opinion polls had indicated that he would give the Conservatives a national lead over Labour.[128] Heseltine attracted sufficient support from the parliamentary party in the first round of voting to force the contest to a second ballot.[129] Although Thatcher initially stated that she intended to contest the second ballot,[129] after consultation with her Cabinet she decided to withdraw.[124][130][131]

Thatcher was succeeded by John Major, who oversaw an upturn in Conservative support in the 17 months leading up to the next general election, which was held on 9 April 1992. Major led the Conservatives to their fourth successive general election victory,[132] but Thatcher's support for Major weakened in later years.[133]

Later years

Thatcher retained her parliamentary seat in the House of Commons as MP for Finchley for two years, returning to the backbenches after leaving the premiership; no subordinate role in government was appropriate.[134] She retired from the House at the 1992 election, aged 66, saying that leaving the Commons would allow her more freedom to speak her mind.[135]Post-Commons

After leaving the House of Commons, Thatcher became the first former Prime Minister to set up a foundation; it closed down in 2005 because of financial difficulties.[136] She wrote two volumes of memoirs: The Downing Street Years, published in 1993 and The Path to Power published in 1995.In August 1992 Thatcher called for NATO to stop the Serbian assault on Goražde and Sarajevo to end ethnic cleansing and to preserve the Bosnian state. She compared the situation in Bosnia to "the worst excesses of the Nazis", and warned that there could be a "holocaust" there.[137] She made a series of speeches in the Lords criticising the Maastricht Treaty,[135] describing it as "a treaty too far" and stated "I could never have signed this treaty".[138] She cited A. V. Dicey, when stating that since all three main parties were in favour of revisiting the treaty, the people should have their say.[139]

From 1993 to 2000, Lady Thatcher was Chancellor of the College of William and Mary in Virginia. From 1992 to 1999 she was also Chancellor of the University of Buckingham, the UK's only private university, which she had opened in 1975.[140]

After Tony Blair's election as Labour Party leader in 1994, Thatcher praised Blair in an interview as "probably the most formidable Labour leader since Hugh Gaitskell. I see a lot of socialism behind their front bench, but not in Mr Blair. I think he genuinely has moved."[141]

In the 2001 general election, Lady Thatcher supported the Conservative general election campaign but did not endorse Iain Duncan Smith in public as she had done previously for John Major and William Hague. In the Conservative leadership election shortly after, she supported Iain Duncan Smith because she believed he would "make infinitely the better leader" than Kenneth Clarke.[142]

In March 2002 Thatcher published Statecraft: Strategies for a Changing World, detailing her thoughts on mainly international relations and dedicated to Ronald Reagan. She claimed there would no peace in the Middle East until Saddam Hussein was toppled and said if he was found to be involved in the attacks on 11 September 2001, war was right. She also said Israel must trade land for peace as part of an equitable settlement. Regarding the European Union, she wrote that it was "fundamentally unreformable" and "a classic utopian project, a monument to the vanity of intellectuals, a programme whose inevitable destiny is failure". She argued that Britain should renegotiate its terms of membership and if this failed Britain should leave the EU and join the North American Free Trade Area. This book was serialised in The Times on 18 March. Having dominated the media all week with her views on the EU, on 23 March she announced that on the advice of her doctors she would cancel all planned speaking engagements and accept no more.[143]

Since 2003

Sir Denis Thatcher died on 26 June 2003. At his funeral service on 3 July[144] she paid tribute to him, saying "Being Prime Minister is a lonely job. In a sense, it ought to be—you cannot lead from a crowd. But with Denis there I was never alone. What a man. What a husband. What a friend".[145]On 11 June 2004 Thatcher attended the state funeral service for former US President Ronald Reagan.[146] She delivered her eulogy via videotape; in view of her failing mental faculties following several small strokes, the message had been pre-recorded several months earlier.[147] Thatcher then flew to California with the Reagan entourage, and attended the memorial service and interment ceremony for the president at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library.[148]

Thatcher attends the Washington memorial service marking the 5th anniversary of the 11 September 2001 attacks, pictured with Dick Cheney and his wife

In 2006 Thatcher attended the official Washington, D.C. memorial service to commemorate the fifth anniversary of the 11 September 2001 attacks on the United States. She was a guest of the US Vice President, Dick Cheney, and met with US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice during her visit.[151]

In February 2007 she became the first living Prime Minister of the United Kingdom to be honoured with a statue in the Houses of Parliament. The bronze statue stands opposite that of her political hero, Sir Winston Churchill,[152] and was unveiled on 21 February 2007 with Lady Thatcher in attendance; she made a rare and brief speech in the members' lobby of the House of Commons, responding: "I might have preferred iron – but bronze will do ... It won't rust."[152] The statue shows her as if she were addressing the House of Commons, with her right arm outstretched.[153]

Lady Thatcher was invited back to Number 10 in late November 2009 to attend the unveiling of an official portrait by the artist Richard Stone,[154] an unusual honour for a living ex-Prime Minister.[155] Stone had previously painted portraits of the Queen and the Queen Mother.[154]

Thatcher suffered several small strokes in 2002 and was advised by her doctors not to engage in any more public speaking.[156] After collapsing at a House of Lords dinner, she was admitted to St Thomas' Hospital in central London on 7 March 2008 for tests.[157] Her daughter Carol has recounted ongoing memory loss.[158] In November 2009, a text message from the Canadian transport minister about the death of a pet cat called 'Thatcher' almost caused a diplomatic incident.[159]

At the Conservative Party conference 2010, the newly installed Prime Minister David Cameron announced he would be seeking to invite Lady Thatcher back to Downing Street on her 85th birthday with a party at 10 Downing Street, to be attended by past and present ministers. Lady Thatcher was forced to pull out of the celebration at the last minute after being taken ill with a bout of flu.[160][161]

Legacy

| Part of the Politics series on |

| Thatcherism |

|---|

| Politics Portal |

As the individualistic credo expressed above took hold of Thatcher's Britain, egalitarian concerns dwindled. Andy Beckett commented: "Authorities on poverty rates and income distributions differ as to precisely when the optimum moment of equality in Britain came, but some statistics leap out. The Gini coefficient, a common measure of income inequality, reached its lowest level for British households in 1977. The proportion of individual Britons below the poverty line did the same in 1978. Social mobility, the likelihood of someone becoming part of a different class from their parents, peaked in the Callaghan era. The egalitarian Britain of the Callaghan years and its social trends were relentlessly reversed in the Thatcher years and beyond, so that Britain in the 1970s was probably more equal than it had ever been before, and certainly more than it has ever been since."[163]I think we have gone through a period when too many children and people have been given to understand "I have a problem, it is the Government's job to cope with it!" or "I have a problem, I will go and get a grant to cope with it!" "I am homeless, the Government must house me!" and so they are casting their problems on society and who is society? There is no such thing! There are individual men and women and there are families and no government can do anything except through people and people look to themselves first. It is our duty to look after ourselves and then also to help look after our neighbour and life is a reciprocal business and people have got the entitlements too much in mind without the obligations...[162]

To her supporters Margaret Thatcher remains a figure who revitalised Britain's economy, impacted the trade unions, and re-established the nation as a world power.[164] Yet Thatcher was also a controversial figure, her premiership marked by high unemployment and social unrest,[164] and many critics fault her economic policies for the unemployment level.[165] Speaking in Scotland in April 2009, before the 30th anniversary of her election as prime minister, Thatcher declared: "I regret nothing", and insisted she "was right to introduce the poll tax and to close loss-making industries to end the country's 'dependency culture'."[166]

Critics have regretted her influence in the abandonment of full employment, poverty reduction and a consensual civility as bedrock policy objectives. Many recent biographers have been critical of many aspects of the Thatcher years and Michael White writing in New Statesman in February 2009 wondered if the ' hubristic collapse of the free-market model of capitalism that she promoted [had] dealt her another blow. Who was it who first removed the seat belts and airbags from the safe-but-boring Volvo that the West built after 1945? 'Her freer, more promiscuous version of capitalism' in Hugo Young's phrase is reaping a darker harvest."[167]

Honours

Margaret Thatcher's arms. The admiral represents the Falklands War, the image of Sir Isaac Newton her background as a chemist and her birth town Grantham.

US President George H. W. Bush awards Thatcher the Presidential Medal of Freedom, 1991

In 1999 Thatcher was among 18 included in Gallup's List of Widely Admired People of the 20th century, from a poll conducted of Americans. In a 2006 list compiled by New Statesman, she was voted 5th in the list of "Heroes of our time".[173] She was also named a "Hero of Freedom" by the libertarian magazine Reason.[174] In the Falkland Islands, Margaret Thatcher Day is marked every 10 January, commemorating her visit on this date in 1983, seven months after the military victory;[175][176] the decision was taken by the Falkland Islands legislature in 1992.[177] Thatcher Drive in Stanley, the site of government, is named for her. In South Georgia, Thatcher Peninsula, where the Task Force troops first set foot on Falklands soil, bears her name.[177]

Thatcher has been awarded numerous honours from foreign countries. In 1990, she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honour awarded by the United States. She was given the Republican Senatorial Medal of Freedom, Ronald Reagan Freedom Award, and named a patron of the Heritage Foundation,[178] which also established the Margaret Thatcher Center for Freedom in 2005.[179] She was awarded the Grand Order of King Dmitar Zvonimir, the fourth-highest state order of the Republic of Croatia.

Cultural depictions

Cultural depictions of Margaret Thatcher have featured in a number of television programmes, documentaries, films and plays; among the most notable depictions of her are Patricia Hodge in The Falklands Play (2002) and Lindsay Duncan in Margaret (2009). She was also the inspiration for a number of protest songs.[180][181][182][183][184]Thatcher was lampooned by satirist John Wells in multiple formats. Wells collaborated with Richard Ingrams on the spoof Dear Bill letters which ran as a column in Private Eye magazine, were published in book form and were then adapted into a West End stage revue as Anyone for Denis? – starring Wells as Thatcher's hapless husband Denis. The stage show yielded a 1982 TV special directed by Dick Clement. Although the Private Eye column, books, stage show and TV special were all ostensibly about Thatcher's husband, this was partly a comedic device to poke fun at Thatcher and followed a similar pattern established by Wells and Ingrams in the 1960s when they had lampooned Prime Minister Harold Wilson through a Private Eye column, books and a West End revue titled Mrs Wilson's Diary using Wilson's wife as the device to mock the Labour Premier. In 1979, Wells was commissioned by comedy producer Martin Lewis to write and perform on a comedy record album titled The Iron Lady: The Coming Of The Leader on which Thatcher was portrayed by comedienne and noted Thatcher impersonator Janet Brown. The album consisted of skits and songs. It was released by Logo Records

11:51 PM

11:51 PM

Wikipedia

Wikipedia

Posted in:

Posted in:

0 comments:

Post a Comment